Brief Notes on Neubig's Tutorial 0~3: Part B

1. Tutorial 1 (Cont.) - Build Uni-gram language model

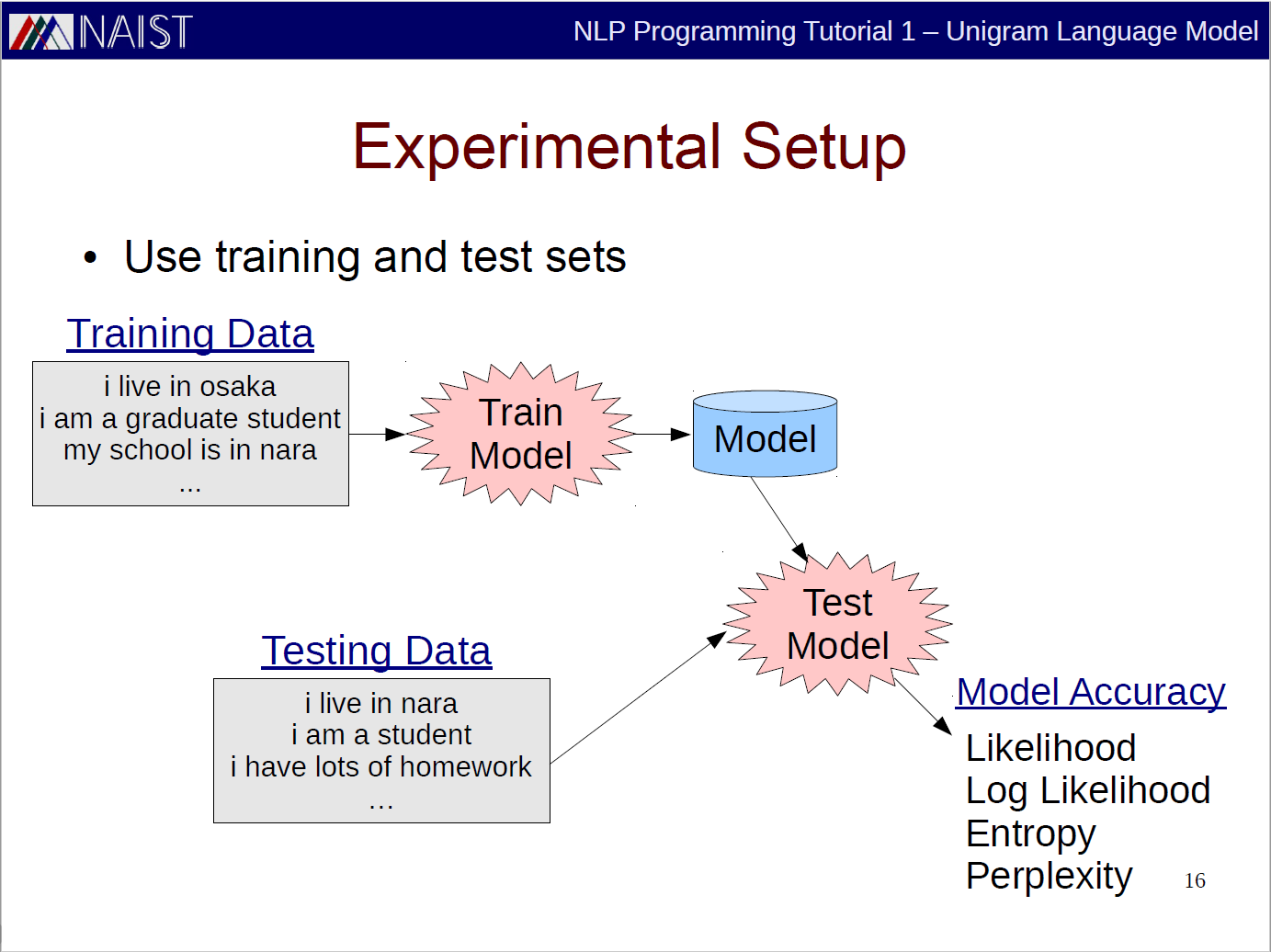

In this section, we follow the Experimental Setup slide to do our coding practice.

We strictly follow the Exercise slide as well since it tells us where to find our training and testing data.

How to create a uni-gram language model? Let us first review the formula to estimate a statistical language models. If we are going to use an n-gram model for modeling language, and assume we have a vocabulary of size \(\vert \mathcal{V} \vert\), then ideally we should have the total number of \(\vert \mathcal{V} \vert^n\) parameters (the \(\theta_{w_{i+n} \vert w_{i+1}, \dots, w_{i+n-1}}\)). Since we are doing maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), we can get the estimator as:

\[P(w_{i+n} \vert w_{i+1}, \dots, w_{i+n-1}) = \theta_{w_{i+n} \vert w_{i+1}, \dots, w_{i+n-1}} = \frac{Count(w_{i+1}, \dots, w_{i+n})}{\sum_{w'_{i+n} \in \mathcal{V}} Count(w_{i+1}, \dots, w'_{i+n})}\]So for the uni-gram model we practice ourself to estimate, we can get the estimator as:

\[P(w_i) = \theta_{w_i} = \frac{Count(w_i)}{\sum_{w'_i \in \mathcal{V} Count(w'_i)}}\]For uni-gram model, we have \(\vert \mathcal{V} \vert\) parameters, each for a word. For estimation and other kinds of learning, we should do 3 stuffs:

- Train the model on a training set.

- Evaluate the model on a test set based on some evaluation metric. (Entropy, perplexity, coverage etc.)

- If the model has hyperparameters (which is not the parameter of the model that could be learned from training set), we can validate different settings of hyperparameters on a validation set or development set.

Comments. For any new practical tasks you will encounter in the future, you should firstly find out where and what is your training set, validation set and test set, which is the data of your experiment and “fuel” of your algorithms. Then, try to understand the data format and judge whether is it suitable for your learning problem; for example, is data listed one example a line? Or for supervised learning, is data provide supervised label within the same line of the example with certain separate like “\(\vert \vert \vert\)”.

Luckily, Neubig has provided us with the training data at data/wiki-en-train.word and test data for computing entropy and coverage at data/wiki-en-test.word and test/01-train-input.txt and test/01-test-input.txt.

Note that, we should train the model over tokenized data. Tokenization is a necessary preprocessing step when dealing with letter-based languages, such as, English, German, French etc. Tokenization means to normalize the raw text into tokens which is the smallest element of a language, like words but also consists of punctuations and special tokens e.g. ~, !, $ etc. and combined words e.g. ‘ll, ‘re, ‘t etc. as in I’ll, you’re and won’t.

Training a uni-gram language model

The algorithm should first go with constructing a vocabulary, and then a map or dict in python to hold each word as key and frequency as value. And we should provide interface with query about a uni-gram parameter \(\theta_{w_i}\), which returns the division of \(w_i\)’s frequency and the total frequency of each word in vocabulary.

'''

1. construct vocab. count frequency

2. interface for querying uni-gram

'''

import argparse

from collections import defaultdict

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("-trainPath", type=str, default="../../data/wiki-en-train.word")

parser.add_argument("-testPath", type=str, default="../../data/wiki-en-test.word")

parser.add_argument("-cut_freq", type=int, default="0")

parse = parser.parse_args()

vocab = defaultdict(lambda: 0)

class LanguageModel:

def __init__(self, filePath, cut_freq=0):

assert filePath not None, "filePath should be given!"

self.vocab = defaultdict(lambda: 0)

self.filePath = filePath

self.cut_freq = cut_freq

def creatVocab(self):

filePath = self.filePath

with open(filePath, 'r') as f:

for line in f.readline():

for word in line.split():

self.vocab[word] += 1

self.totolFreq = 0

for word, freq in self.vocab.iteritems():

if freq > cut_freq:

self.totolFreq += freq

def queryFreq(self, word):

if self.vocab[word] > cuf_freq:

prob = self.vocab[word] * 1.0 / self.totlFreq

return self.vocab[word], prob

else:

# return self.vocab[word], .0

return self.vocab[word], 1./len(self.vocab)

if __name__ == "__main__":

filePath = parse.trainPath

cut_freq = parse.cut_freq

unigram_lm = LanguageModel(trainPath, cut_freq)

unigram_lm.createVocab()

In the above code, a class LanguageModel is created, and several functionalities could be integrated into that class. Here, only two functionalities are provided:

createVocab(): which create a dictionary {word: freq} and count the total frequency of uni-gram withcut_freqthreshold to ignore word below that value.queryFreq(str): which will return the word freq and its uni-gram probability.

Evaluate the uni-gram language model

This part relates to the evaluation or test of the statistical language model. Actually, there is no very promising ways to evaluate a probabilistic generative model. Entropy over a held-out data set can somehow judge the uncertainty of the predictive power of the model.

Comments. A generative model models a joint distribution over data points as phenomenon; since its generative nature, we can sample from a generative model to get data which are similar to those data for training the model. Given a generative model \(P(x)\), the entropy is defined as expected negative log likelihood: \(\sum_x -P(x) \log P(x)\).

Our language model \(P(w_{i+n} \vert w_{i+1}, w_{i+2}, \dots, w_{i+n-1})\) is actually a generative model. You may ask: Wait a moment, why? Because the probabilistic form is a conditional obviously. However, the phenomenon we are modeling is sentences or word sequences, so the generative model is over the whole sentence or word sequence \(w_1, w_2, \dots, w_n\). And the conditionals are just decomposed parts of the joint probability.

Therefore, given a language model, we can sample sentences from it and the sentence will somehow look naturally. As a result, a good language model can generate a given natural sentence with high probability, this is how we compute the probability of a sentence with the trained model in a held-out test set. So the overall performance of the trained model on a held-out set can be used for evaluation. We use entropy as a measure of the model’s uncertainty of generate a held-out test set.

Caveat. Dear friends, not until I run the program and get the entropy result that I found I have totally mistaken the formula to compute entropy.

Entropy: 4.8348240665e-05 Coverage: 1.0, this is the result I get, where the entropy is extremely small! My fault is: I should not use the above entropy definition to compute the entropy over a sampled test data.

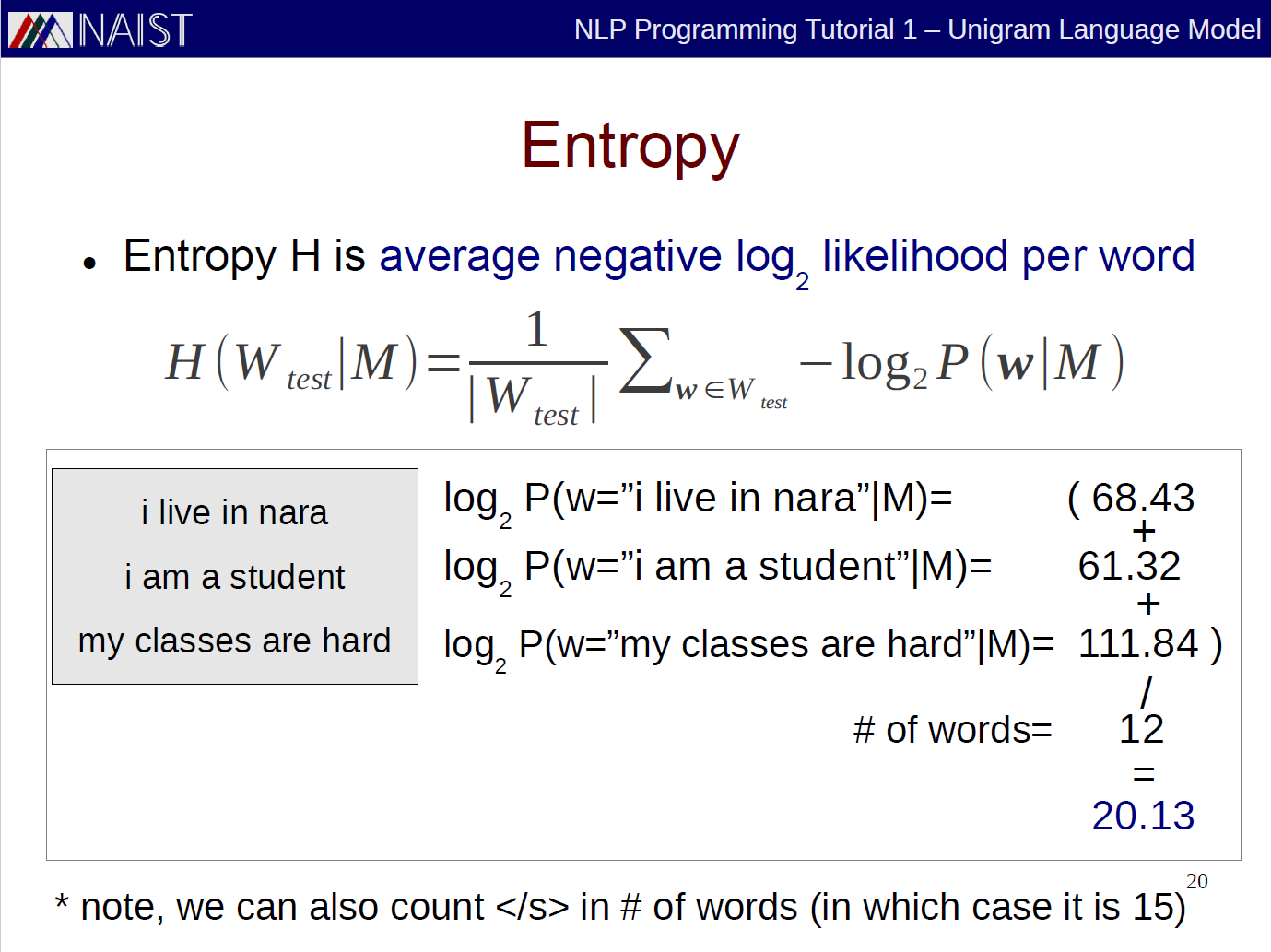

Let us take a closer look at the formula \(\sum_x -P(x) \log P(x)\). We must understand that the sum is over all possible value of \(x\) in the sample space. For natural language, the sample space is all the possible combination of word sequences. So it is just impossible to do the summation over all the possible sequences, but a small subset of those sequences which is our test set. So the entropy becomes empirical entropy with uniform distribution over sequences in the dataset, and the formula should be:

\[\frac{1}{\vert \mathcal{D_{test}} \vert} \sum - \log P(x)\]However, I still get the run entropy compared to that of Neubig’s slide:

Actually, I did not wrong again, but computed the entropy per sentence while Neubig computed the entropy per word. The reason I end up computing entropy per sentence is that I regard our model as a generative model on sentence.

We could also regard the model as generative model on word. Since it is uni-gram, the model is just \(P(w_i)\). And according to the definition of entropy, we get that: \(\sum_{w} - P(w) \log P(w)\). So the empirical entropy will be computed as:

\[\frac{1}{\vert W_{test} \vert} \sum_{w \in W_{test}} - \log_2 P(w)\]Here is a detail we should concern about! When we compute the logarithm, we can use \(\log_2\) or \(\log_e\). They are actually play the same role in evaluation. However, make sure you use the same logarithm when evaluating different language modeling methods.

I did wrong here U_U

If the held-out set is denoted as \(\mathcal{D}\), we can compute the entropy by:

entropy = .0

for sentence in D:

entropy_per_sentence = - P(w_1) P(w_2) ... P(w_n) [log P(w_1) + log P(w_2) + ... + log P(w_n)]

entropy += entropy_per_sentence

So we can add this functionality of entropy computation to our LanguageModel class.

class LanguageModel:

# __init__

# createVocab

# queryFreq

def computeEntropy(self, testFilePath):

assert testFilePath is not None

word_count = 0

entropy = .0

with open(testFilePath, 'r') as f:

for line in f.readlines():

entropy_per_sentence = .0

log_sum = .0

multiply = 1.

for word in line.split():

word_count += 1

_, prob = self.queryFreq(word)

log_sum += math.log(prob)

# multiply *= prob

entropy_per_sentence = multiply * log_sum

entropy += entropy_per_sentence

return entropy / word_count

Another metric is provided to evaluate our language model - coverage. This hints on the coverage of the original training data. The formula to compute coverage is very simple:

\[Coverage(\mathcal{D}) = \frac{\sum_{x \in \mathcal{D}} KnownWordCount(x)}{\sum_{x \in \mathcal{D}} WordCount(x)}\]Let us add this functionality to our LanguageModel class as well.

class LanguageModel:

# __init__

# createVocab

# queryFreq

# computeEntropy

def computeCoverage(self, testFilePath):

assert testFilePath is not None

known_word_count = 0

word_count = 0

with open(testFilePath, 'r') as f:

for line in f.readlines():

words = line.split()

word_count += len(words)

for word in words:

if word in self.vocab:

known_word_count += 1

return know_word_count * 1. / word_count

So the entropy and coverage I finally get are the following, it can be wrong! How about yours?

Entropy: 8.98133921742 Coverage: 1.0

Dealing with unknown words

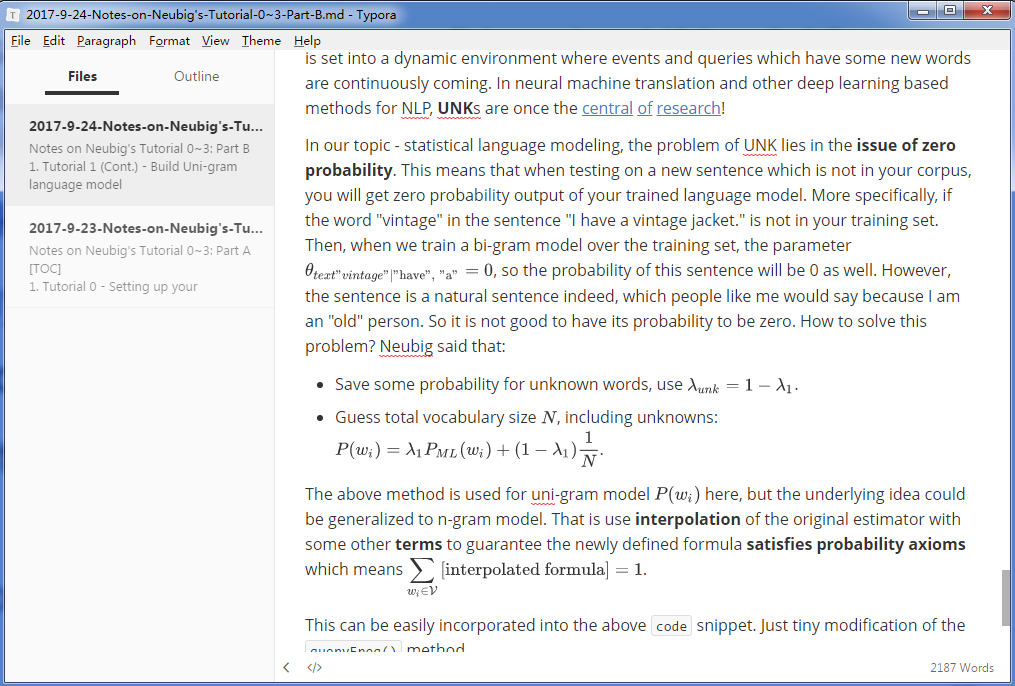

Unknown words (UNKs) are the most common problem in all fields of natural language processing, since no matter how big your training set is, you may always encounter new words which are not in your training set. This problem becomes severe when your system is set into a dynamic environment where events and queries which have some new words are continuously coming. In neural machine translation and other deep learning based methods for NLP, UNKs are once the central of research!

In our topic - statistical language modeling, the problem of UNK lies in the issue of zero probability. This means that when testing on a new sentence which is not in your corpus, you will get zero probability output of your trained language model. More specifically, if the word “vintage” in the sentence “I have a vintage jacket.” is not in your training set. Then, when we train a bi-gram model over the training set, the parameter \(\theta_{text{"vintage"} \vert \text{"have", "a"}} = 0\), so the probability of this sentence will be 0 as well. However, the sentence is a natural sentence indeed, which people like me would say because I am an “old” person. So it is not good to have its probability to be zero. How to solve this problem? Neubig said that:

- Save some probability for unknown words, use \(\lambda_{unk} = 1 - \lambda_1\).

- Guess total vocabulary size \(N\), including unknowns: \(P(w_i) = \lambda_1 P_{ML}(w_i) + (1 - \lambda_1) \frac{1}{N}\).

The above method is used for uni-gram model \(P(w_i)\) here, but the underlying idea could be generalized to n-gram model. That is use interpolation of the original estimator with some other terms to guarantee the newly defined formula satisfies probability axioms which means \(\sum_{w_i \in \mathcal{V}} \text{[interpolated formula]} = 1\).

This can be easily incorporated into the above code snippet. Just tiny modification of the queryFreq() method.

class LangaugeModel():

# __init__

# createVocab()

def queryFreq():

lambda1 = 0.95

if self.vocab[word] > cuf_freq:

prob = self.vocab[word] * 1.0 / self.totlFreq

return self.vocab[word], prob * lambda1

else:

# return self.vocab[word], .0

return self.vocab[word], 1./len(self.vocab) * (1- lambda1)

2. Bonus: use Typora and other markdown tools to write notes

I Really, Really, Really, Really recommend you guys to use Typora a lovely, simple, easy-to-use, cross-platform markdown editor to write notes in your daily life.

I used to use stackedit.io, as well, a WISIWIG markdown editor like Typora. However, it could not provide basic file management usage like in Typora:

You can see the leftmost navigator with Files and Outline for the file management of current chosen directory and outline of your current markdown file. All my love about Typora comes from Jiaming Song who is the author of the theme of my blog and a young researcher.

Don’t feel pain to write in markdown, with which the grammar is as natural as you take notes on your notebook with a pen/pencil. I mostly use the following marks.

- Different level of title or section title.

#is the 1st level,##is the second,###the third,####the fourth etc. - Comments or notes between-lines. Use

>to mark the beginning of that line. - Code snippets. Code snippets. Use double “

" for in-line codes and use double "``” for cross-line codes. - URLs. Use

[content](url)to show the effect like content. - Math formula. This is my favorite, just type

Latexgrammar between dollars$$ \sum_x x^2 $$which will show \(\sum_x x^2\). Beautiful hah!

I simple guide to markdown is given here as a Hello! file.

However, if you want to use Google Drive or other cloud drive to hold your .md files. You can use stackedit.io which is much lightweight and has natural interface with many mainstream cloud drives.

When you get familiar with the markdown and the editor as well as the Latex grammar for typing math. You can start to write diary or blogs as well as take notes online. Together with git and github you can as well manage your notes and blogs easily and geekly! Hope you enjoy blogging and taking notes.