Notes on Neubig's Tutorial 0~3: Part C

This post is about a natural language processing task or application titled word segmentation (WS), which is very essential in Chinese and Japanese etc. language processing. Usually, WS will function as the very beginning part in the processing pipeline of raw text. The content of the post hopes to cover the following 3 parts: 1). the basic definition of WS, to make strangers familiar with this task; 2). problem formulation, which deals with how we could use the probability score of a language model and transfer the WS problem as a classic dynamic programming problem algorithmically; 3). Viterbi algorithm to solve the dynamic programming problem.

1. What is word segmentation?

Actually, this question has been introduced in the tutorial slides. In the third page, Neubig says “word segmentation adds spaces between words”. This is a very straightforward explanation. However, why languages like Chinese and Japanese need word segmentation? The reason can bear both simple and complex explanations.

The simple reason is that languages with characters (象形文字) instead of letters will not use space to explicitly distinguish word meanings.

The complex reason is that languages have its own writing systems (书写系统), which have been evolved to incorporate some regularities and rules to make written language easy to read and understand. The writing systems of Chinese and other character-based languages does not require spaces to separate words with independent meanings. Here, you can know that: every language phenomenon is evolvable according to social development and convention formulation. So if you understand social culture better, you will be a good language user.

More formally, we can define the word segmentation problem as a structured prediction problem. The input of the prediction problem is a natural language sequence which is usually a sentence, \(w_1, w_2, \dots, w_n \), and the output is the input sequence with augmented separators inserted between characters, \(w_1, w_2, s, \dots, s, w_n \), where \(s\) denotes separator.

Comment.

Here to be more clearer, we regularize the usage of the word: word and character, and we use “word” to denote “phrase in Chinese” like “祖国”, “花朵”, and use “character” to denote each specific Chinese character like “祖”, “国” etc.

Let us use a more specific example, the input could be “山东省因居太行山以东而得名”, and the output of the WS system would be “山东省s因s居s太行山s以东s而s得名”, where “s” is the separator as well.

Structured prediction.

Structured prediction (SP) is a prediction problem which predicts the structure in the input. More specifically, the input would be a combinatorial structure, i.e. a sequence, a graph structure etc. and the output would a combinatorial structure as well, which augments the input structure with latent structural informations, e.g. labels in POS tagging, parse trees in syntactic parsing, links in link prediction over graph etc. To be honest, SP problem can be much complex and does not have a sound definition because of the diversity of all kinds of SP problems. If you are interested in SP problems, you can read Hal Daume’s PhD thesis here.

2. Word segmentation: problem formulation

This part first casts WS problem as a machine learning problem with certain training corpus. We still use a model \(P_\theta (y \vert x)\) to describe the probabilistic relationship between the input sentence \(x\) and the output augmented sentence \(y\).

Then, we regard the problem of learning as estimating the parameters of the model, \(\theta\); and prediction as finding the best \(y\) regarding to the model \(y^* = argmax_y P_\theta (y \vert x)\) given \(x\). Since \(y\) has combinatorial structure, we should use a search algorithm to smartly traverse the search space and effectively find the best \(y^*\).

We will specifically discuss how to use a language model as \(P_\theta\) to score the \(y\)s in output space, and an efficient dynamic programming algorithm Viterbi algorithm to search the best \(y^*\).

Word segmentation and other structured prediction problem, e.g. named entity recognition, part-of-speech tagging etc. can be formulated as a two-stage process:

Caveat.

I want to insert a caveat here. Since the two-stage solution to structured prediction problems is not the only one we can embrace upon, however, the two-stage paradigm is the most famous and popular one since it has motivate many research development in probabilistic graphical models which is an approach with a group of algorithms and theories to do probabilistic machine learning. There is another way to do structured prediction which integrates learning and inference (search) within a same stage, it is titled SEARN as a nickname for “search and learn”, which brings us with a sequential decision making (kind of reinforcement learning) view of structured prediction. (PS: the PhD thesis I mentioned above is on this topic, actually the author is the inventor of SEARN, bravo!)

- Learning stage: we assume a model with the form \(P_\theta(x, y)\) or \(P_\theta(y \vert x)\) with parameter \(\theta\), to learn a scoring rule (which is the probability of the conditional \(P(y \vert x)\)), so we end up learning a scoring rule over output space (search space) \(\mathcal{Y}\).

- Decoding stage: given an estimated model \(P_\theta\), if we are provided with a new \(x\) which is not in the training corpus, we should now predict the corresponding \(y\). To do this, we should solve the optimization problem \(y^* = argmax_y P_\theta(y \vert x)\). This is sometimes called a decoding problem or search problem, where you need to search over exponentially possible combinatorial structures of \(y\).

Note 1.

Here, someone may be curious about why \(P_\theta (x, y)\) can form a scoring rule over the output space \(\mathcal{Y}\), since it is a probability score over the combined space of both \(\mathcal{X}\) and \(\mathcal{Y}\). Since we can transform \(P_\theta\) to be the conditional probability by dividing the marginal \(P(x) = \sum_y P_\theta(x, y)\) to get our dreaming formula \(P(y \vert x) = \frac{P_\theta(x, y)}{\sum_y P_\theta(x, y)}\).

However, we can find that \(argmax_y P(y \vert x) = argmax \frac{P_\theta(x, y)}{P(x)} = argmax P_\theta(x, y)\) since \(x\) is given, thus a constant here with respect to the \(argmax_y\) operator.

I think the above discussion has made it clear how to model a structured prediction problem, or specifically, a WS problem. Next in this section, we are going to consider Chinese word segmentation and use a model \(P_\theta(y \vert x)\) to learn the scoring rule and introduce the decoding algorithm - Viterbi algorithm - in next section.

Note 2.

The two probability forms introduced in the Learning stage consist of two paradigms of predictive modeling: the discriminative model and the generative model. This two words “discriminative” and “generative” has some ambiguity in some claims or statements. Considering the statement, “Discriminative model is not just probabilistic classifiers and can still have generative power”, how you understand it? My division of discriminative/generative model is that when you are doing predictive modeling (maybe you can sometimes call it supervised learning) - that is you are given an input \(x\) and an output \(y\), you learn a model across all such training samples, and when new \(x\) is given, the model and its related prediction algorithm is asked to predict \(y\) - if you model a joint distribution over both input and output space \(P(x, y)\) you are using a generative model, or if you model a conditional distribution with examples in input space as condition \(P(y \vert x)\) you are doing discriminative modeling.

So the generative models can generate samples in input space as well whereas the discriminative models can only generate sample in output space, which could be class labels or a combinatorial structure, I say in the latter case, the discriminative model has generative power.

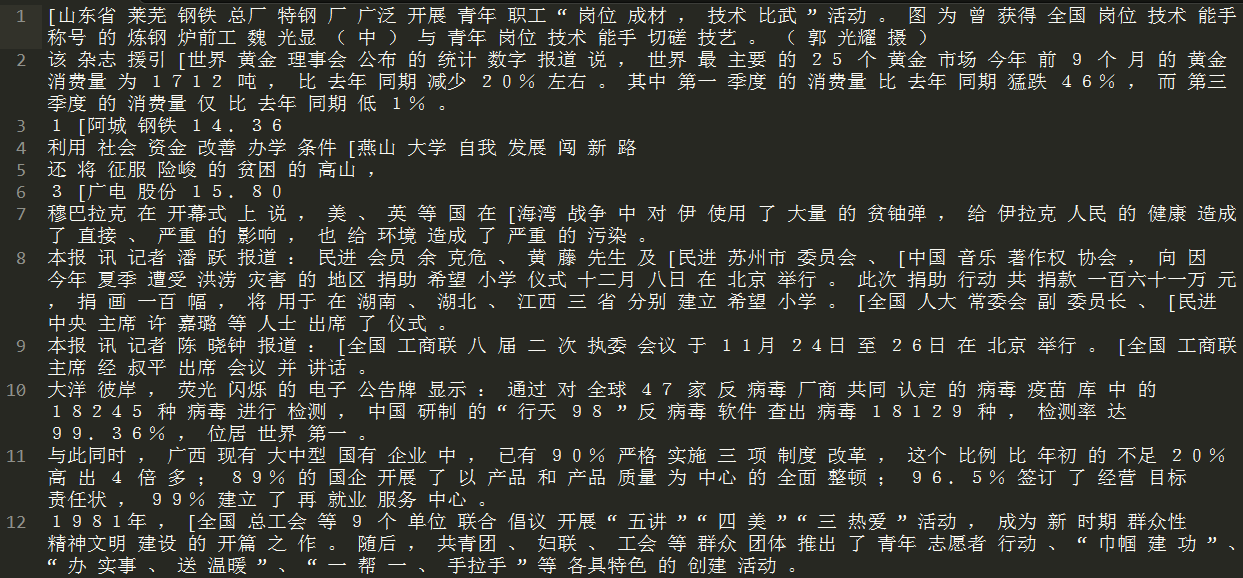

Firstly, let us be familiar with our training data, how they looked?

-

The training data is just Chinese sentences which have been segmented.

-

The test data consists of lines, each with an test example and its gold reference separated by

|||.

Comment.

Here I want make us know that we are going to use the Chinese word segmentation dataset which I cleaned from

人民日报corpus. In my github repo of our NLP tutorial, I have added filermrb=199812.rawin the/datafolder, and have preprocessed the raw data into train and test files:rmrb-train.tokandrmrb-test.tok. In the experiment, I would like to use the Chinese corpus instead of the original Japanese one.

2.1 Why a language model as a scoring rule?

Let us see how a language model can be used as a scoring rule for WS problem. In the previous discussion, we know that we need to learn a model \(P_\theta (y \vert x)\), so that given the input unsegmented sentence, we can have a scoring rule - the probability - of possible segmentations \(y\)s over \(x\).

However, since a language model is not a conditional distribution of the form \(P (y \vert x)\) as we have discussed above, we cannot directly use a language model. But if we change the form of conditional to be: \(P(y \vert x) = \frac{P(y) P(x \vert y)}{P(x)}\), we can find that since we constrain \(y\) within the space of inserting separators into \(x\), so for the \(y\), the probability of getting the \(x\) is actually 1, that is \(P(x \vert y) = 1\) in the above equation. So we can get a new scoring rule only determined by \(P(y)\) (Note that here we ignore the denominator because it is the same with respect to the same \(x\)).

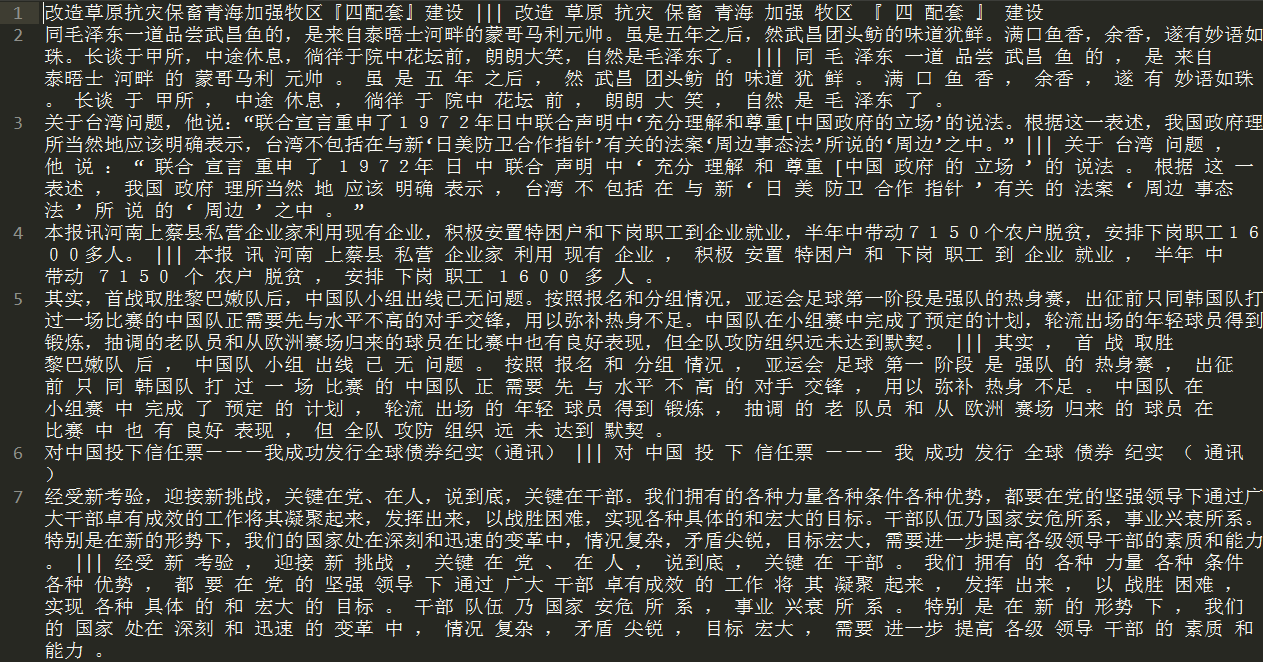

Another view of using a language model as a scoring rule is very intuitive, which is demonstrated in Neubig’s slide below:

Comment.

Here I would like to emphasize a mistake I made when I am trying to understand why language model here could help. The mistake is that I am confused with the minimum granularity of certain natural language the LM wants to model. For example, for English, the smallest language phenomenon we are modeling is the words/tokens of English, i.e. cat, dog, ‘s, ‘ll, etc. However, for Chinese, the smallest language phenomenon might be characters like “疼”, “晓” etc. Or if we focus on dealing with “词组” in Chinese, the smallest phenomenon we are modeling should be phrase like “饺子”, “海鲜” etc. Here, we are going to use phrase-level language model which is trained over segmented Chinese sentences for us to score different segmentations of a given sentence, so that the LM can recognize good segmentations from bad ones thus acts as a scoring rule.

2.2 How to model the decoding problem using LM score?

So after using the method learned from Tutorial 1, we can train our phrase-level language model over the rmrb-train.tok file. And now, we get the trained unigram language model \(P(\cdot)\) where the \(\cdot\) can be any phrase in Chinese. If the phrase exists in the training corpus, we can get its probability estimation, or otherwise, we will get a smoothed estimation for this unknown word.

Now, let us embrace the decoding stage - to deal with the decoding problem (actually, it is a search problem). The first stupid method we can use to solve the decoding problem is to use exhaustive search. That is, given an unsegmented sentence \(x\), we can enumerate all possible segmentations \(y\)s and use the scoring rule to judge \(P(y)\), and choose \(y^*\) with the biggest \(P(y)\). This is a very stupid method, how can we improve it?

Comment.

Actually, this is a search algorithm design problem. Since I am poor in algorithm design and analysis, the following story maybe weird for you to read with intuition. Forgive me about that, and I promise I am doing the best of myself.

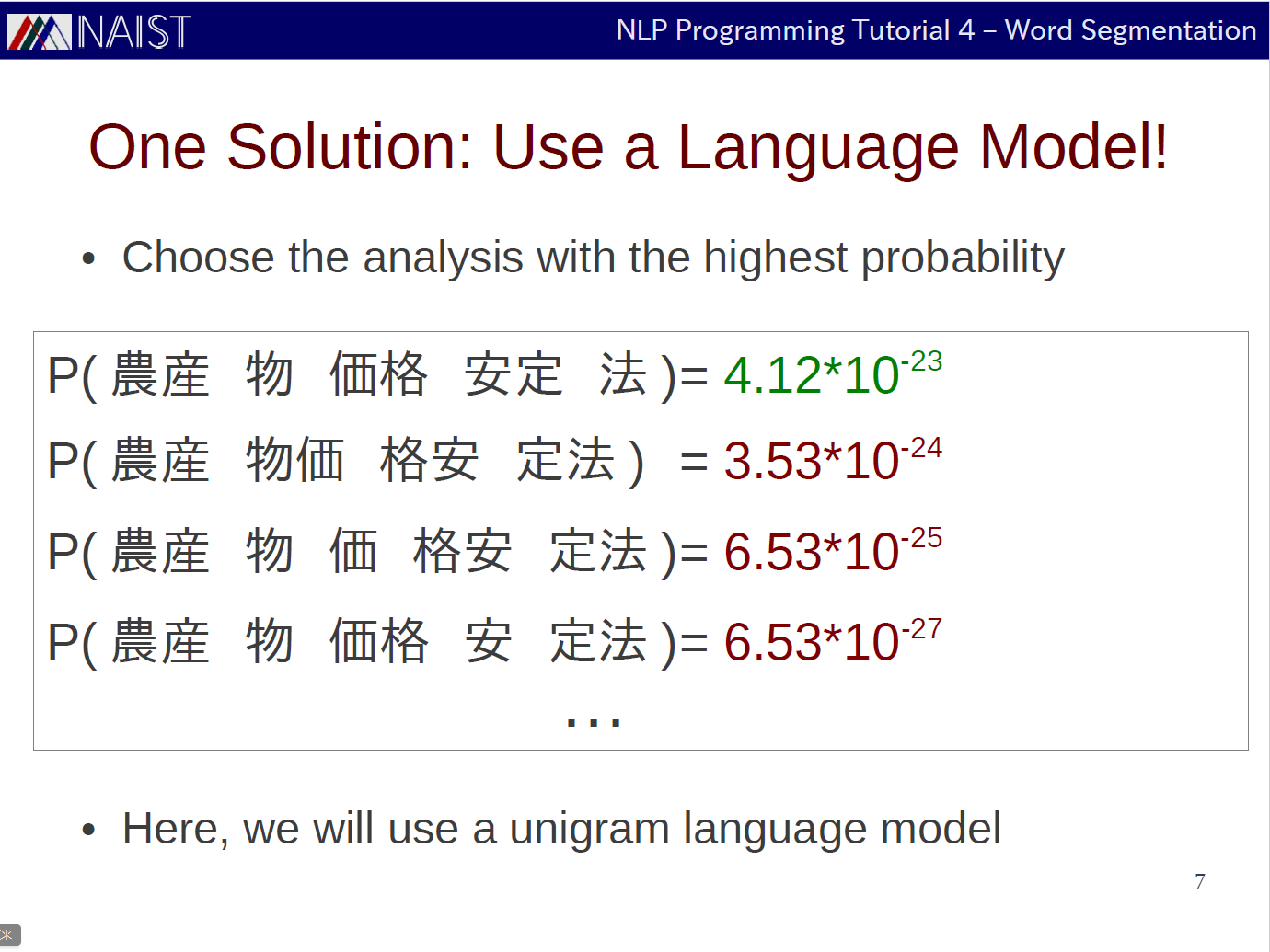

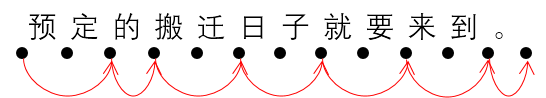

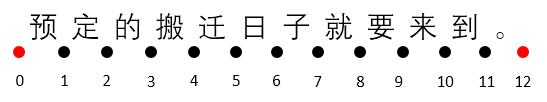

We can formulate the problem of finding the best segmentation as finding a path that connects those black nodes in the following graph.

The above 3 figures represent:

- Nodes separate each character in the sentence.

- An optimal path which achieves the golden segmentation. (Golden segmentation means the best segmentation or the reference segmentation.)

- The reference segmentation.

In terms of the path, I would claim that:

- Each path represents a certain segmentation of the original sentence. (This is obvious!)

- All possible paths equal to all possible segmentations of the sentence. (This is not that obvious, but intuitively you can accept this, right?)

There are constraints for the path. That is:

- Each edge of that path should not cross with others;

- those edges that consist a path are adjacent.

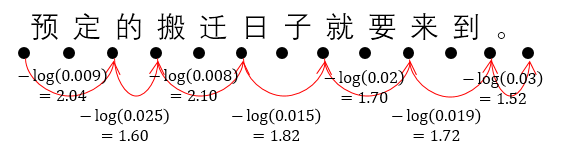

After we abstract the segmentation problem as a path finding problem, we should now find the usage of the trained language model \(P(\cdot)\). It is very obvious to say that the language model can give weights between any two nodes, that is the edge with weight, like below:

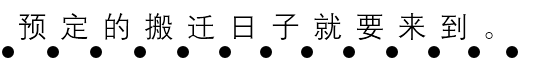

The sum of the path is the negative log likelihood of the sentence “预订 的 搬迁 日 就要 来到 。”. That is:

\[\begin{align} & -\log P(\text{预订, 的, 搬迁, 日子, 就要, 来到, 。}) \\ &= -\log P(\text{预订}) - \log P(\text{的}) - \log P(\text{搬迁}) - \log P(\text{日子}) - \log P(\text{就要}) - \log P(\text{来到}) - \log P(\text{。}) \\ &= 2.04 + 1.60 + 2.10 + 1.82 + 1.70 + 1.72 + 1.52 \\ &= 10.78 \end{align}\]According to the above example, we define the weight of each edge equals to the negative log likelihood of the phrase covered by the edge. So to find the best segmentation, we are supposed to find the smallest sum path.

2.3 Solve the path finding problem by Viterbi algorithm

The nature of Viterbi algorithm is to take advantage of the optimal substructure of the problem, and use Dynamic Programming to efficiently compute optimal sub-solutions; and find the best solution by backward tracking.

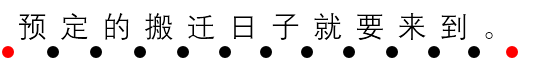

Given the sentence to be segmented, we can draw the nodes to separate each character. Moreover, we can find that the path should start and end with the red nodes in the following figure, that is the beginning and ending of the node sequence.

We index the nodes as following:

Suppose that for each node with index \(i\), we 1). save the smallest possible sum \(s_i\) to that node and 2). record the edge with the node index \(n_i\) that brings with this sum (which is the edge \((n_i, i)\)). Since there are \(i-1\) possible edges that could be linked from previous \(i-1\) nodes, so we can have a recursive formula to compute \(s_i\):

\[s_i = min_{1 \leq j \leq i-1} [s_j + P(j, i)], n_i = argmin_{1 \leq j \leq i-1} s_j\]The above formula assumes that when computing \(s_i\) for node \(i\), previous nodes have saved the optimal sub-solution. Here \(P(j, i)\) means the substring composed by characters from \(j\) to \(i-1\).

After computing from left-to-right, we can get the optimal sum at each node and the best adjacent edge that can lead to the sum. So if we start backward tracking from node 12, we can find a path all the way down to node 0, and this is the smallest sum path of the all sentence. The python psudocode of the algorithm might be the following.

# const to denote +inf

INF = 10000

# 1. Train the language model, and get a dictionary:

unigram_prob = {'string' : probability}

# 2. Given an unsegmented sentence encoded by unicode (follow the instruction on the 5th slide of Neubig)

str_utf8 # you can access each char by indexing str_utf8[i] to get the i-th character

# 3. Initialize a list to hold sub-optimal sums s_i and another list to hold previous edge n_i

length = len(str_utf8)

s = [INF for i in range(length)]

s[0] = 0.

n = [0 for i in range(length)]

# 4. loop to compute s_i and n_i

for end_node_idx in range(1, len):

for start_node_idx in range(0, end_node_idx):

# find the best previous adjacent edge

unigram = str_utf8[start_node_idx:end_node_idx]

tmp_sum = s[start_node_idx] + unigram_prob[unigram]

# compare which is sum is smaller

if tmp_sum < s[end_node_idx]:

s[end_node_idx] = tmp_sum

n[end_node_idx] = start_node_idx

# 5. backward tracking to find the path

start_node_idx = end_node_idx = length - 1

str_list = []

while n[start_node_idx] != 0:

start_node_idx = n[end_node_idx]

word = str_utf8[start_node_idx : end_node_idx + 1]

str_list.append()

end_node_idx = start_node_idx

segmentation = list(reversed(str_list))

Appendix

The discussion paper has not been decided yet. Following are some papers which have some impact on the community. To be honest, for every task like word segmentation, many methods have been tried out, Bayesian, log-linear, neural networks etc. So the key point is to grasp each of those techniques behind specific tasks, so that you can have more dimensions when you are solving a new task in your job or research career.

Reference

- Chinese Word Segmentation without Using Lexicon and Hand-crafted Training Data, Maosong Sun et al. 1998.

- Chinese Word Segmentation and Named Entity Recognition: A Pragmatic Approach, 2006. Jianfeng Gao, et al. Computational Linguistics.

- Optimizing Chinese Word Segmentation for Machine Translation Performance, WMT 2008. Manning’s group.

- Max-Margin Tensor Neural Network for Chinese Word Segmentation, ACL 2014. Baobao Chang’s group at Peking Univ.